Post by : Amit

Photo : X / Autocar

South Korea’s Housing Market Faces Major Overhaul with Landmark Deregulation Plan

In a move that could profoundly reshape South Korea’s real estate landscape, the country’s Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport (MOLIT) has unveiled an ambitious package of deregulation measures aimed at reviving a sluggish housing market, speeding up redevelopment, and stimulating private sector participation in construction.

Announced on July 16, the proposal includes sweeping changes such as lifting price ceilings on newly built apartments, easing restrictions on property redevelopment, expanding the criteria for floor area ratio (FAR) relaxations, and restoring key incentives for private builders. If implemented, it would mark the most significant liberalization of South Korea’s housing policy in nearly a decade.

The reform plan comes amid growing anxiety over stagnant home construction activity, declining housing starts, and falling public interest in redevelopment projects due to excessive red tape. Officials argue that deregulation is urgently needed to expand housing supply, cool inflationary pressures, and address the deepening imbalance between housing demand and delivery timelines.

A Housing Market in Paralysis

South Korea's housing market has remained under pressure for the better part of the last two years. While prices soared during the pandemic, recent policy tightening and rising interest rates have dampened buyer sentiment. Meanwhile, developers—faced with strict price caps, density controls, and permit hurdles—have delayed or canceled numerous projects.

At the center of the problem lies the so-called “housing redevelopment bottleneck.” Even in areas where demand is high, it often takes more than a decade to push a project from approval to completion. According to MOLIT, 87 percent of existing reconstruction projects in the pipeline are stalled or progressing at a crawl.

This regulatory gridlock has had cascading effects on both supply and affordability. While demand continues to rise, particularly in metropolitan areas like Seoul, the inability to build fast or flexibly has pushed the market into dysfunction.

The Deregulation Blueprint

At the heart of MOLIT’s plan is the elimination of the price ceiling for newly built homes—currently one of the most controversial housing regulations in Korea. The ceiling was originally introduced to prevent speculative price inflation and to keep housing affordable in prime areas. But critics argue that it has backfired by discouraging private builders, who have little incentive to undertake projects that limit their profit margins.

By abolishing the cap, the ministry hopes to make new housing development more attractive to private firms, allowing them to set prices based on market dynamics rather than government formulas.

Another major reform involves the restoration of floor area ratio (FAR) incentives. FAR governs how much space can be built relative to the size of a plot of land. In recent years, tighter FAR rules have made redevelopment projects less profitable, especially in high-demand zones.

MOLIT’s new proposal would reintroduce FAR flexibility for projects that meet criteria such as rental housing provision, eco-friendly building standards, and urban renewal guidelines—effectively rewarding builders for contributing to public housing goals or sustainable design.

Also on the table: faster permitting for reconstruction, streamlined approval processes for existing homeowners looking to redevelop, and stronger legal rights for project initiators to overcome local opposition. These changes could significantly reduce timelines for urban renewal projects, which often become mired in neighborhood disputes and bureaucratic holdups.

Experts Divided: Boon for Builders, or Risk to Stability?

While the deregulation plan has been welcomed by developers and market-friendly economists, it has also sparked concerns about potential unintended consequences—especially in a country with a history of property speculation and price bubbles.

“The government is trying to revive supply momentum, but removing guardrails like price caps carries real risk,” said Professor Park Hye-jin, a housing economist at Korea University. “Without adequate oversight, developers might flood the market with expensive units, further marginalizing middle-income buyers.”

Park added that deregulation must go hand-in-hand with targeted public housing initiatives, especially in areas where land values are high but income diversity is limited.

On the other hand, the Korea Housing Builders Association (KHBA) lauded the proposed changes, saying they will “restore balance” to a market that has been distorted by well-meaning but ultimately harmful policies.

“Investors and construction firms have been paralyzed,” said KHBA spokesperson Lee Sang-woo. “This is the kind of decisive policy intervention we’ve been waiting for.”

Seoul and the Metropolitan Challenge

Nowhere will the reforms matter more than in Seoul and its surrounding metropolitan areas, where more than half of South Korea’s population resides—and where housing scarcity has become a politically volatile issue.

The capital’s dense urban fabric has long made redevelopment a complicated affair. While tower cranes dot the skyline, the bulk of new apartment supply comes from long-delayed reconstruction projects. Local governments often impose additional layers of bureaucracy, and local resident groups can stall construction for years.

MOLIT is working with Seoul City to implement a pilot model that incorporates the new deregulation tools into a handful of strategic sites. These include districts like Gangbuk, Songpa, and Yeongdeungpo, where stalled redevelopment has coincided with steep rent increases and outmigration of younger residents.

If these pilots succeed, they could serve as a roadmap for scaling deregulation nationwide.

Broader Economic Implications

Housing is not just a social issue—it’s an economic driver. Real estate accounts for more than 15% of South Korea’s GDP when construction and related industries are included. The current slump in housing starts has dragged down growth projections, with ripple effects felt in steel, cement, home furnishings, and even banking.

By unblocking stalled projects and incentivizing new ones, the deregulation plan could revive job creation, increase housing stock, and stimulate upstream sectors. Analysts at Hana Securities estimate that a 20% uptick in new project approvals could boost quarterly GDP by as much as 0.3%.

Yet the plan must also grapple with financial system risk. Many Korean developers have leveraged heavily to acquire land and pre-sell units. A sudden influx of deregulated projects—especially if not matched by buyer demand—could strain smaller firms and put pressure on banks already navigating a rising-rate environment.

A Political Bet with Voter Impact

With South Korea’s general elections looming in 2026, the deregulation plan also has undeniable political stakes. Housing affordability and supply have been persistent electoral issues, with younger voters and middle-class families expressing deep dissatisfaction with the status quo.

The ruling People Power Party hopes the reform package will shift public perception—away from the bureaucratic inertia that has characterized past governments and toward a more pragmatic, pro-growth housing vision.

Still, the plan must clear multiple stages, including National Assembly review, local government buy-in, and public consultations. Labor unions, civil society groups, and renters' associations have already voiced opposition, demanding more protections and government-built affordable housing alongside any deregulation.

What Next?

MOLIT says it will finalize the deregulation blueprint by September, after which the changes will be rolled out in stages. The initial focus will be on metropolitan areas with the most stalled projects, followed by secondary cities where population growth is rising.

The ministry has also promised to publish impact assessments every six months, tracking metrics like housing starts, price inflation, and regional equity. These data points will be crucial in judging whether deregulation serves its intended purpose—or simply shifts wealth upward.

For now, South Korea stands at a housing crossroads. Deregulation could unlock desperately needed supply, boost economic growth, and modernize aging neighborhoods. But unless carefully calibrated, it could also invite speculative fervor and deepen social divides.

If executed with transparency and accountability, MOLIT’s bold move could become a defining chapter in South Korea’s real estate evolution—one that balances growth with responsibility in an era of urgent housing challenges.

MOLIT, South Korea

Advances in Aerospace Technology and Commercial Aviation Recovery

Insights into breakthrough aerospace technologies and commercial aviation’s recovery amid 2025 chall

Defense Modernization and Strategic Spending Trends

Explore key trends in global defense modernization and strategic military spending shaping 2025 secu

Tens of Thousands Protest in Serbia on Anniversary of Deadly Roof Collapse

Tens of thousands in Novi Sad mark a year since a deadly station roof collapse that killed 16, prote

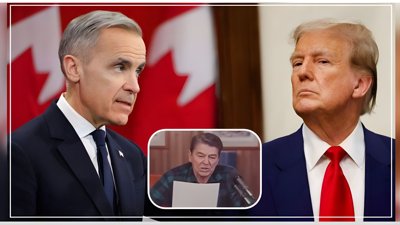

Canada PM Carney Apologizes to Trump Over Controversial Reagan Anti-Tariff Ad

Canadian PM Mark Carney apologized to President Trump over an Ontario anti-tariff ad quoting Reagan,

The ad that stirred a hornets nest, and made Canadian PM Carney say sorry to Trump

Canadian PM Mark Carney apologizes to US President Trump after a tariff-related ad causes diplomatic

Bengaluru-Mumbai Superfast Train Approved After 30-Year Wait

Railways approves new superfast train connecting Bengaluru and Mumbai, ending a 30-year demand, easi